PLC Knowledge Round-Up: Essential Reading for Electrical Engineers!

PLC Knowledge Round-Up: Essential Reading for Electrical Engineers!

I. Definition and Classification of PLCs

PLC, or Programmable Logic Controller, is a new generation of universal industrial control devices. It's based on microprocessors and integrates computer technology, automatic control technology, and communication technology. Designed for industrial environments, PLCs feature easy-to-understand programming using a "natural language" oriented towards control processes and users. They are characterized by simplicity, ease of operation, and high reliability.

Evolved from relay sequential control, PLCs are centered around microprocessors and serve as versatile automatic control devices. Let's delve into the specifics:

1. Definition

A PLC is a digital electronic system designed for industrial applications. It utilizes a programmable memory to store instructions for operations such as logical computation, sequential control, timing, counting, and arithmetic. By interfacing with digital and analog inputs and outputs, PLCs control various mechanical equipment and production processes. Both PLCs and their peripheral devices are designed to integrate seamlessly with industrial control systems and to facilitate functional expansion.

2. Classification

PLC products come in a wide variety with differing specifications and performance capabilities. They are broadly classified based on structural form, functional differences, and the number of I/O points.

2.1 Classification by Structural Form

PLCs can be categorized into integral and modular types based on their structural form.

(1) Integral PLC

Integral PLCs house components such as the power supply, CPU, and I/O interfaces within a single cabinet. They are known for their compact structure, small size, and affordability. Small-sized PLCs typically adopt this integral structure. An integral PLC consists of a basic unit (also known as the main unit) with different I/O points and an expansion unit. The basic unit contains the CPU, I/O interfaces, an expansion port for connecting to I/O expansion units, and interfaces for connecting to a programmer or EPROM writer. The expansion unit, on the other hand, only contains I/O and power supply components, without a CPU. The basic unit and expansion unit are usually connected via a flat cable. Integral PLCs can also be equipped with special function units, such as analog units and position control units, to expand their capabilities.

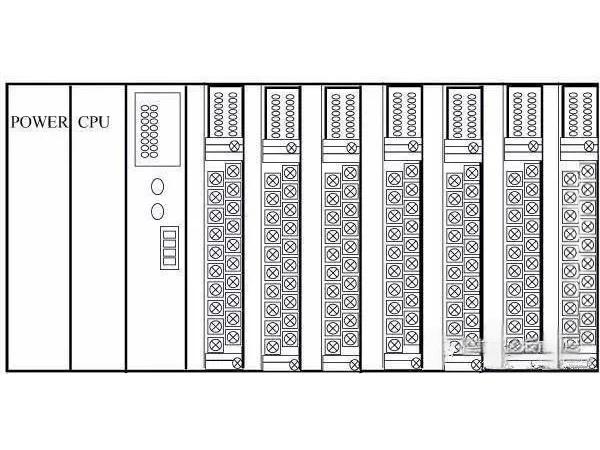

(2) Modular PLC

Modular PLCs feature separate modules for each component, such as CPU modules, I/O modules, power supply modules (sometimes integrated within the CPU module), and various function modules. These modules are mounted on a framework or backplane. The advantage of modular PLCs lies in their flexible configuration, allowing for the selection of different system scales as needed. They are also easy to assemble, expand, and maintain. Medium and large-sized PLCs generally adopt a modular structure.

Additionally, some PLCs combine the characteristics of both integral and modular types, forming what is known as a stacked PLC. In stacked PLCs, components such as the CPU, power supply, and I/O interfaces are independent modules connected via cables and can be stacked layer by layer. This design not only offers flexible system configuration but also allows for a compact size.

2.2 Classification by Function

Based on their functional capabilities, PLCs can be divided into three categories: low-end, mid-range, and high-end.

(1) Low-end PLC

Low-end PLCs possess basic functions such as logical operations, timing, counting, shifting, self-diagnosis, and monitoring. They may also include a limited amount of analog input/output, arithmetic operations, data transfer and comparison, and communication functions. These PLCs are primarily used for single-machine control systems involving logical control, sequential control, or a small amount of analog control.

(2) Mid-range PLC

In addition to the functions of low-end PLCs, mid-range PLCs offer stronger capabilities in analog input/output, arithmetic operations, data transfer and comparison, number system conversion, remote I/O, subroutines, and communication networking. Some may also feature interrupt control and PID control functions, making them suitable for complex control systems.

(3) High-end PLC

High-end PLCs, in addition to the capabilities of mid-range PLCs, include advanced functions such as signed arithmetic operations, matrix computations, bit logic operations, square root calculations, and other special function operations. They also feature table creation and table transfer capabilities. High-end PLCs boast enhanced communication and networking functionalities, enabling large-scale process control or the formation of distributed network control systems, thereby achieving factory automation.

2.3 Classification by I/O Points

Depending on the number of I/O points, PLCs can be classified into small, medium, and large categories.

(1) Small PLC

Small PLCs have fewer than 256 I/O points, feature a single CPU, and utilize 8-bit or 16-bit processors. Their user memory capacity is typically below 4KB.

(2) Medium PLC

Medium PLCs have between 256 and 2048 I/O points, employ dual CPUs, and have a user memory capacity ranging from 2KB to 8KB.

(3) Large PLC

Large PLCs boast over 2048 I/O points, utilize multiple CPUs, and are equipped with 16-bit or 32-bit processors. Their user memory capacity ranges from 8KB to 16KB.

Worldwide, PLC products can be categorized into three major regional types: American, European, and Japanese. American and European PLC technologies were developed independently, resulting in distinct differences between their products. Japanese PLC technology, introduced from the United States, inherits certain characteristics from American PLCs but focuses on small-sized PLCs. While American and European PLCs are renowned for their medium and large-sized offerings, Japanese PLCs are famous for their small-sized counterparts.

II. Functions and Application Fields of PLCs

PLCs combine the advantages of relay-contactor control and the flexibility of computers. This unique design赋予了PLCs numerous unparalleled features compared to other controllers.

1. Functions of PLCs

As a universal industrial automatic control device centered around microprocessors and integrating computer technology, automatic control technology, and communication technology, PLCs offer a multitude of advantages. These include high reliability, compact size, strong functionality, simple and flexible program design, versatility, and easy maintenance. Consequently, PLCs find extensive applications in fields such as metallurgy, energy, chemicals, transportation, and power generation, emerging as one of the three pillars of modern industrial control (alongside robots and CAD/CAM). Based on the characteristics of PLCs, their functional forms can be summarized as follows:

(1) Switching Logic Control

PLCs possess robust logical computation capabilities, enabling them to achieve various simple and complex logical controls. This is the most fundamental and widely applied domain of PLCs, replacing traditional relay-contactor control.

(2) Analog Control

PLCs are equipped with A/D and D/A conversion modules. The A/D module converts analog quantities from the field—such as temperature, pressure, flow, and speed—into digital quantities. These digital quantities are then processed by the microprocessor within the PLC (as microprocessors can only handle digital quantities) and subsequently used for control. Alternatively, the D/A module converts digital quantities back into analog quantities to control the controlled object, thereby enabling PLCs to exert control over analog quantities.

(3) Process Control

Modern medium and large-sized PLCs typically feature PID control modules, enabling closed-loop process control. When a variable deviates during the control process, the PLC calculates the correct output using the PID algorithm, thereby adjusting the production process and maintaining the variable at the setpoint. Currently, many small-sized PLCs also incorporate PID control functionality.

(4) Timing and Counting Control

PLCs boast strong timing and counting capabilities, capable of providing dozens, hundreds, or even thousands of timers and counters. The timing duration and counting values can be arbitrarily set by the user when writing the user program, or by operators on-site through a programmer. This enables timing and counting control. If users need to count high-frequency signals, they can opt for high-speed counting modules.

(5) Sequential Control

In industrial control, sequential control can be achieved through PLC step instructions or shift register programming.

(6) Data Processing

Modern PLCs are not only capable of performing arithmetic operations, data transfer, sorting, and table look-up but can also conduct data comparison, data conversion, data communication, data display, and printing. They possess robust data processing capabilities.

(7) Communication and Networking

Most modern PLCs incorporate communication and network technologies, featuring RS-232 or RS-485 interfaces for remote I/O control. Multiple PLCs can be networked and communicate with each other. Signal processing units of external devices can exchange programs and data with one or more programmable controllers. Program transfer, data file transfer, monitoring, and diagnostics can be achieved through communication interfaces or communication processors, which utilize standard hardware interfaces or proprietary communication protocols to facilitate program and data transfer.

2. Application Fields of PLCs

Currently, PLCs are widely employed both domestically and internationally across various industries, including iron and steel, petroleum, chemicals, power, building materials, mechanical manufacturing, automobiles, light textiles, transportation, environmental protection, and cultural entertainment. Their applications can be broadly categorized as follows:

(1) Switching Logic Control

This is the most fundamental and extensively applied domain of PLCs, replacing traditional relay circuits to achieve logical and sequential control. PLCs can be used for single-machine control as well as multi-machine group control and automated production lines, such as injection molding machines, printing machines, stapling machines, combination machine tools, grinding machines, packaging production lines, and electroplating assembly lines.

(2) Analog Control

In industrial production processes, numerous continuously varying quantities—such as temperature, pressure, flow, liquid level, and speed—are analog quantities. To enable PLCs to handle analog quantities, A/D and D/A conversions between analog and digital quantities must be realized. PLC manufacturers produce accompanying A/D and D/A conversion modules to facilitate analog control applications for PLCs.

(3) Motion Control

PLC can be used for rotary or linear motion control. In terms of control system configuration, early applications directly connected position sensors and actuators to switch I/O modules. Nowadays, specialized motion control modules are generally employed. These modules can drive single-axis or multi-axis position control for stepper motors or servo motors. Almost all major PLC manufacturers' products worldwide feature motion control capabilities, which are widely used in various machinery, machine tools, robots, elevators, and other applications.

(4) Process Control

Process control refers to closed-loop control of analog quantities such as temperature, pressure, and flow. It has extensive applications in fields like metallurgy, chemical engineering, heat treatment, and boiler control. As industrial control computers, PLCs can be programmed with a variety of control algorithms to accomplish closed-loop control. PID control is a commonly used regulation method in closed-loop control systems. Both medium and large-sized PLCs are equipped with PID modules, and currently, many small-sized PLCs also feature this functional module. PID processing generally involves running a dedicated PID subroutine.

(5) Data Processing

Modern PLCs are equipped with mathematical operations (including matrix computation, function computation, logical operations), data transfer, data conversion, sorting, table look-up, and bit manipulation functions. They can perform data acquisition, analysis, and processing. These data can be compared with reference values stored in memory to carry out specific control operations or transmitted to other intelligent devices via communication functions. They can also be printed and tabulated. Data processing is typically used in large-scale control systems, such as unmanned flexible manufacturing systems, and in process control systems, such as those in papermaking, metallurgy, and the food industry.

(6) Communication and Networking

PLC communication encompasses communication between PLCs and between PLCs and other intelligent devices. With the development of computer control, factory automation networks have advanced rapidly. All PLC manufacturers place great emphasis on the communication capabilities of PLCs and have introduced their respective network systems. Recently produced PLCs are equipped with communication interfaces, making communication very convenient.

III. Basic Structure and Working Principle of PLCs

As an industrial control computer, PLCs share similarities in structure with ordinary computers. However, differences arise due to varying usage scenarios and objectives.

1. Hardware Components of PLCs

The basic structure diagram of a PLC host is shown in the figure below: [Figure]

In the diagram, the PLC host consists of a CPU, memory (EPROM, RAM), input/output units, peripheral I/O interfaces, communication interfaces, and a power supply. For integral PLCs, all these components are housed within the same cabinet. In modular PLCs, each component is independently packaged as a module, and the modules are connected via a rack and cables. All parts within the host are interconnected through power buses, control buses, address buses, and data buses. Depending on the requirements of the actual control object, various external devices are configured to form different PLC control systems.

Common external devices include programmers, printers, and EPROM writers. PLCs can also be equipped with communication modules to communicate with higher-level machines and other PLCs, thereby forming a distributed control system for PLCs.

Below is an introduction to each component of the PLC and its role, to help users better understand the control principles and working processes of PLCs.

(1) CPU

The CPU is the control center of the PLC. Under the control of the CPU, the PLC coordinates and operates orderly to achieve control over various on-site equipment. Composed of a microprocessor and a controller, the CPU can perform logical and mathematical operations and coordinate the work of various internal components of the control system. The controller manages the orderly operation of all parts of the microprocessor. Its primary function is to read instructions from memory and execute them.

(2) Memory

PLCs are equipped with two types of memory: system memory and user memory. System memory stores system management programs, which users cannot access or modify. User memory stores compiled application programs and work data states. The part of user memory that stores work data states is also known as the data storage area. It includes input/output data image areas, preset and current value data areas for timers/counters, and buffer zones for storing intermediate results.

PLC memory primarily includes the following types:

Read-Only Memory (ROM)

Programmable Read-Only Memory (PROM)

Erasable Programmable Read-Only Memory (EPROM)

Electrically Erasable Programmable Read-Only Memory (EEPROM)

Random Access Memory (RAM)

(3) Input/Output (I/O) Modules

① Switching Input Module

Switching input devices include various switches, buttons, sensors, etc. PLC input types can be DC, AC, or both. The power supply for the input circuit can be externally provided, or in some cases, supplied internally by the PLC.

② Switching Output Module

The output module converts the TTL-level control signals output by the CPU when executing the user program into signals required on the production site to drive specific equipment, thereby actuating the execution mechanism.

(4) Programmer

The programmer is an essential external device for PLCs. It allows users to input programs into the PLC's user program memory, debug programs, and monitor program execution. Programmatically, programmers can be categorized into three types:

Handheld Programmer

Graphical Programmer

General Computer Programmer

(5) Power Supply

The power supply unit converts external power (e.g., 220V AC) into internal working voltage. The externally connected power supply is transformed into the working voltage required by the PLC's internal circuits (e.g., DC 5V, ±12V, 24V) through a dedicated switch-mode voltage regulator within the PLC. It also provides a 24V DC power supply for external input devices (e.g., proximity switches) (for input points only). The power supply for driving PLC loads is provided by...

(6) Peripheral Interfaces

Peripheral interface circuits connect handheld programmers or other graphical programmers, text displays, and can form a PLC control network via the peripheral interface. PLCs can connect to computers using a PC/PPI cable or MPI card through an RS-485 interface, enabling programming, monitoring, networking, and other functions.

2. Software Components of PLCs

PLC software comprises system programs and user programs. System programs are designed and written by PLC manufacturers and stored in the PLC's system memory. Users cannot directly read, write, or modify them. System programs typically include system diagnostic programs, input processing programs, compilation programs, information transfer programs, and monitoring programs, among others.

User programs are compiled by users using PLC programming languages based on control requirements. In PLC applications, the most critical aspect is using PLC programming languages to write user programs to achieve control objectives. Since PLCs are specifically developed for industrial control, their primary users are electrical technicians. To cater to their traditional habits and learning capabilities, PLCs primarily employ dedicated languages that are simpler, more understandable, and more intuitive compared to computer languages.

Graphical Instruction Structure

Explicit Variables and Constants

Simplified Program Structure

Simplified Application Software Generation Process

Enhanced Debugging Tools

3. Basic Working Principle of PLCs

The PLC scanning process is mainly divided into three stages: input sampling, user program execution, and output refreshing. As shown in the figure: [Figure]

Input Sampling Stage

During the input sampling stage, the PLC sequentially reads all input statuses and data in a scanning manner and stores them in the corresponding units of the I/O image area. After input sampling is completed, the process moves on to the user program execution and output refreshing stages. In these two stages, even if the input statuses and data change, the statuses and data in the corresponding units of the I/O image area will not be altered. Therefore, if the input is a pulse signal, the pulse width must be greater than one scanning cycle to ensure that the input can be read under any circumstances.

User Program Execution Stage

During the user program execution stage, the PLC always scans the user program (ladder diagram) in a top-down sequence. When scanning each ladder diagram, it first scans the control circuit formed by the contacts on the left side of the ladder diagram. Logical operations are performed on the control circuit in a left-to-right, top-to-bottom order. Then, based on the results of the logical operations, the status of the corresponding bit in the system RAM storage area for the logical coil is refreshed, or the status of the corresponding bit in the I/O image area for the output coil is refreshed, or it is determined whether to execute the special function instructions specified by the ladder diagram.

That is, during the execution of the user program, only the statuses and data of the input points in the I/O image area remain unchanged, while the statuses and data of other output points and soft devices in the I/O image area or system RAM storage area may change. Ladder diagrams positioned higher up will affect the execution results of lower ladder diagrams that reference these coils or data. Conversely, the refreshed statuses or data of logical coils in lower ladder diagrams will only influence higher ladder diagrams in the next scanning cycle.

Output Refreshing Stage

When the user program scan is complete, the PLC enters the output refreshing stage. During this phase, the CPU updates all output latch circuits according to the statuses and data in the I/O image area and drives the corresponding peripherals via the output circuits. This marks the true output of the PLC.

Input/Output Lag Phenomenon

From the PLC working process, the following conclusions can be drawn:

Programs are executed in a scanning manner, resulting in an inherent lag in the logical relationship between input and output signals. The longer the scanning cycle, the more severe the lag.

In addition to the time occupied by the three main working stages—input sampling, user program execution, and output refreshing—the scanning cycle also includes time consumed by system management operations. The time taken for program execution is related to the program length and the complexity of the instruction operations, while other factors remain relatively constant. Scanning cycles are typically on the order of milliseconds or microseconds.

During the nth scan execution, the input data relied upon is the sampled value X obtained during the sampling phase of that scanning cycle. The output data Y(n) is based on both the output value Y(n-1) from the previous scan and the current output value Yn. The signal sent to the output terminal represents the final result Yn after all computations have been executed during this cycle.

The input/output response lag is not only related to the scanning method but also to the arrangement of the program design.